I admit this book made me ponder on success. Over the years, I’ve discovered I don’t share the same opinions with the general public. When a book becomes a huge success, I’m usually part of the minority that didn’t like it. Everyone around me sings praises on how wonderful that book is, how much they enjoyed it and how it changed their life, and I find myself wondering if we are talking about the same book. To draw a comparison, I’d be equally puzzled if someone went to the average burger-and-fries chain and claimed with tears in their eyes they’ve eaten the best food of their lives. So I’ve come to formulate a theory.

My theory is the following. Readers of fiction books can be divided in two categories. The categories have nothing to do with genre preference. The first category is the majority. It consists of those who want to kill a few hours and read something that doesn’t challenge them. They want to be swept away in a fantasy land where everything is easy to accomplish, situations are familiar (read between the lines: exclusive use of clichés in story lines and characters) and everyone is safe. The ones who die are the bad guys and they deserved to die, and a hero is as great and awesome as their writer claims them to be, no proof needed. If the book delivers what the genre promised (i.e. impressive, mindless action, maudlin romance etc) these readers are happy with their share. They are basically trying to escape our reality because it is hard, messy and unfair. I feel for them because I read for the same reason. I want to escape reality. The difference is I don’t want to go to Barbie land because I belong to the second category.

The second category is the minority who wants to be challenged. They expect the fantasy world to be as hard, real and unforgiving as this one. They love a solid set of social rules that might be different than the ones we have, but just as difficult to bend. They don’t want the heroes to be safe and the path familiar. The protagonists need to prove themselves and earn the respect of both their readers and the other characters. There might be dragons in that world, or magic, or advanced technology, but if a character does something stupid, they’ll pay. These readers love realism and hate easy solutions with a passion. They don’t want the heroes to be safe. They want them to be real, and bleed, and ache, and most of all, they want them to grow.

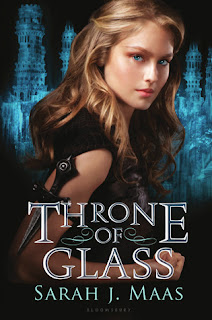

Throne of Glass is wildly popular and unfortunately targets the first category. Instead of writing a review that focuses on the details of the characters and plot, I wish to focus on why the female protagonist fails completely at being the so-called best assassin of that world. Her role as an assassin is the core of both the character and the book, so I want to discuss this.

What does it mean to be an assassin? I’ll write down my thoughts. Assassins belong to a specialised class that undergoes rigorous training, in order to acquire the physical, mental and emotional traits of their role, the most important being strict discipline. They are made immune to hardship by regular exposure to it; rough weather, physical pain, lack of food and water, lack of sleep. Snipers, for example, can stay awake for up to 72 hours during a mission. The mental and emotional training of an assassin is just as strict, creating a ‘one track mind’. Such people ignore every distraction, including verbal provocations, a handsome lass (or lad), unfavourable odds and heart-wrenching pleas for mercy. Depending on the type and universe, we can assume they have a daily routine that includes specialised exercise, perhaps meditation or reciting the beliefs of their sect etc. And I am pretty certain that even if they begin training at a very early age, even the most talented ones don’t make master assassins at the age of 17.

The problem with the Young Adult genre is how easily something is accomplished. Since readers of this genre are often in their teens, they need a protagonist of the same age to identify with. So these books present us with a variety of characters with superhuman powers or ‘master’ status in their field at the ripe age of 16, 17 and 18. These books also conveniently forget to mention the method of achieving master status. (I’ll let you into the secret because I’m feeling generous. You slave away for years at your chosen subject until you grow utterly sick of it, and then you slave away for some more years.) Because every teenager want to be the best, but no-one wants to be seen as an uncool, hard-working nerd, YA novels have these super characters who are ‘chosen’, ‘special’, ‘unique’ etc because reasons. The protagonist Celaena is such a special girl. She is the best assassin there is, but everything she says and does verifies the opposite. Why? Because the writer didn’t want to create a realistic character who IS badass, but rather one who SOUNDS badass. Let me elaborate.

A trained assassin, even a female one, doesn’t care about her looks or what others think of her. She tries to draw as little attention as possible, has a permanent poker face, and is immune to hardship. She’s also immune to the good looks of the Prince and the Captain of the Guard. (By the way, I know that the title ‘Captain of the Guard’ brings to mind a forty-something gruff veteran, but the Captain in question is 22 years old, so that Celaena is spoiled for choice between him and the Prince.) An assassin doesn’t brag, doesn’t expect others to pet her, spoil her or take her side, doesn’t engage in lengthy conversations with her captors, doesn’t get in fits of rage over a game of billiards, and generally doesn’t do any of the things Celaena does. Let’s face it; which teenage girl would identify with the aloof, secretive, cynical, fashion-oblivious hardened soldier that a professional assassin is? None. So in order to create a heroine a teenage girl can identify with, you essentially create another teenage girl who is the best assassin of the land because you, the writer, says so.

With that as a given, I can rant for hours on how implausible Celaena is. The best assassin of the land spends the night before the critical tournament that will determine her freedom or death by reading books until four in the morning. (By the way, since this is a medieval-ish setting, may I point out that back then books were very rare and 99% of people couldn’t read? The books that did exist around that time weren’t meant for recreation; they were usually gargantuan, hand-copied tomes on religion, philosophy and history that made someone develop a headache after ten minutes of reading. But anyway, let’s take for granted that in that fantasy world typography and recreational books already exist and most people can read; it’s a minor blunder compared to other inconsistencies.) The following morning she doesn’t want to get out of bed and complains about the cold floor. Then her next problem is her unfashionable clothes. People sneak in and out of her room at all hours and this terrifying assassin whose fame precedes her just keeps on snoring. She twirls her (blonde) hair around her finger and opens her mouth to show the food she’s been chewing to annoy others. Someone is killing the tournament participants in a brutal way, but when she finds a bag of candy in her room (no note or name on it), she gobbles it down without a worry in the world. She spends her days in front of a mirror or playing the piano or reading, admiring her pretty dresses and wondering why she is not invited at balls. And so on, and so forth. I can continue, but I doubt this will serve any purpose. As I said, those readers who don’t mind the absurdity of the plot and characters will love it, and the ones who can’t abide it will just cringe, like I did.

I find books of the YA genre oversimplified in a dangerous way. Life is not a series of easy, magical solutions. The only place someone can be an assassin, mage, neurosurgeon etc just by claiming they are one, is a video game (or perhaps social media). How about books which show that someone doesn’t have to be the best and coolest in order to be important, or alternatively, showing how hard it is to become the best? How about YA books that deal with second best, or even failure? How about helping a teenager understand that they don’t have to prove something, but should enjoy life instead, because there is plenty of time to discover themselves and their passions along the way?

I am afraid that for me YA has become the equivalent of a warning label. “Danger of wasted time. Read at your own risk.” I honestly hope I am wrong and I just haven’t read the good ones yet.

And another pet peeve of mine. This is the writer.

Now please explain to me why she is on the cover of her own book, because I can’t for the life of me make sense of it.

Leave a Reply